DeBÍ ToCaR MáS GüiRo: The Puerto Rican Instrument from Taínos to Bad Bunny

From the Taíno guajey to the contemporary güiro: we tell you the evolution of this instrument, which is fundamental in rhythms like danza and plena.

—

If there’s one instrument that stands out in DeBÍ TiRAR MáS FOToS, Bad Bunny’s latest album, it’s the güiro. Not only does it delight us with its sweet sound in the plena of Café con ron or in the música jíbara of Pitorro de coco. It also surprises us by carrying the melody in Lo que le pasó a Hawaii, a song in which the instrument demonstrates its versatility and presence.

But the güiro is an instrument many Puerto Ricans grew up with. It reminds us of our grandparents’ house, the Christmas parrandas, and the lechón asa’o. Its fame precedes “Benito, son of Benito” and Ricky Martin, who also made it sound in his hit Pégate.

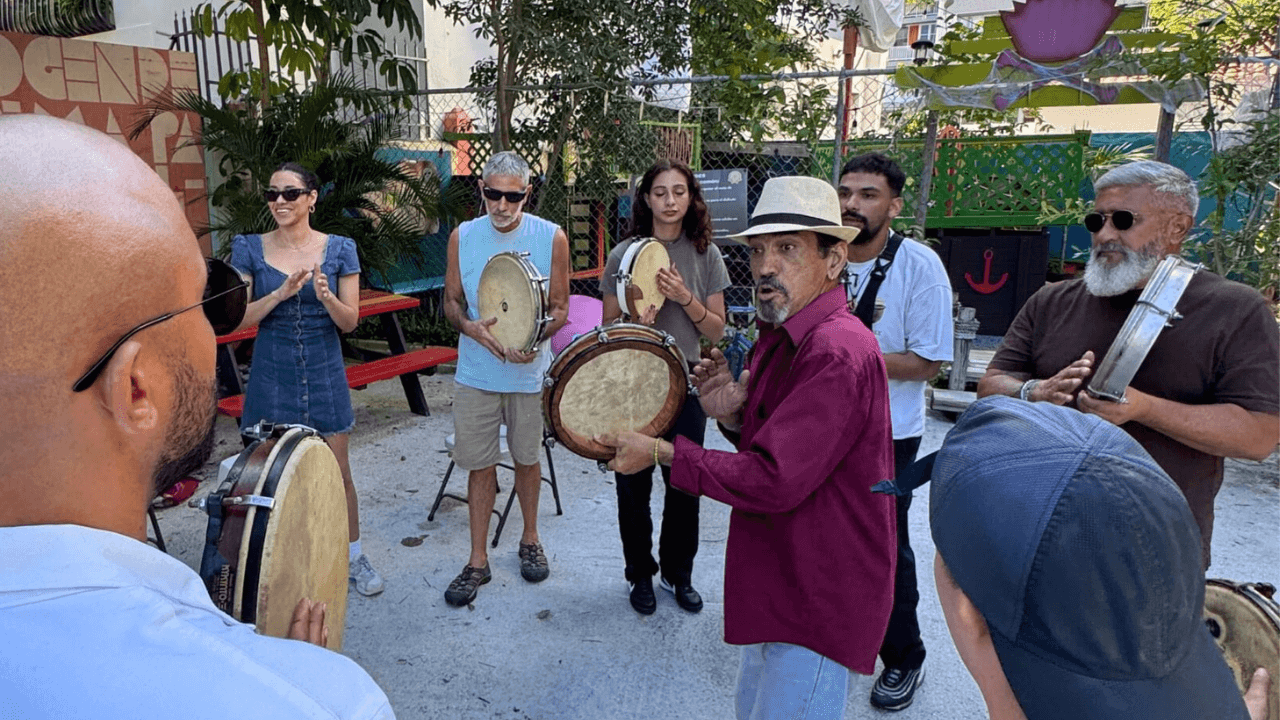

Two emblematic güireros from Puerto Rico join us on this journey through the history of the güiro: Aníbal Alvarado from Peñuelas, the reason why Peñuelas is known as the Capital of the Güiro, and percussionist and historian Rubén Amador Medina, director of the Conservatorio de Artes del Caribe (CAC), a pre-university institution that is a partner of Berklee College of Music.

How is the Puerto Rican güiro made?

The güiro, a Taíno instrument

“The Puerto Rican güiro or güícharo comes to us primarily as an instrument that emerged from the Taíno guajey,” Amador Medina, former director of the Music Program at the Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña (ICP), told Platea. “We know that it won’t necessarily look like what we see today, with fine grooves played with a metal varillero, because they were probably thicker grooves played with a small stick,” he added.

However, the musician said the explanation isn’t that simple, since many cultures have developed percussion instruments similar to the güiro, belonging to the family of scrapers or scraped idiophones. African cultures had similar instruments that could also have influenced what our güiro is today.

- Did you know? Alvarado mentioned there’s a legend that says the güiro was used in Taíno ceremonies to attract rain, since its sound is similar, but it’s a fact difficult to verify historically, noted Amador Medina.

What is worth highlighting is that the güiro unites us as Antilleans, as it’s the foundation of multiple Afro-Caribbean rhythms, including Puerto Rican danza and plena, where it keeps time and provides accents.

“The güiro is a symbol of our Puerto Rican identity, but also of our Caribbean identity. It is a symbol of how Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, and Cuba have a common foundation, and we may be different on the surface, but deep down we are the same people.”

“Without güiro there’s no Cuban son, there’s no cha-cha without the güiro. There’s no merengue without the güira. And there’s no plena, no música jíbara without our güícharo,” emphasized Amador Medina.

What makes the Puerto Rican güiro unique

“The main distinctive feature of the Puerto Rican güiro is that it has a sweeter, softer, more elegant sound” than other scrapers, explained Amador Medina, who has a particular love for the güiro as it was the first instrument he got paid to play as a musician at age 15. It was also the instrument that took him traveling through Europe on a tour with Gíbaro de Puerto Rico, a folkloric company he’s been with for 23 years.

Material: The reasons for the güiro’s sweet sound are because it’s made from a vegetable, in this case the marimbo, and not from metal, like the Dominican güira, for example.

Grooves: It has fine grooves, with multiple thin lines and not thick ones like the Cuban güiro, which has a deeper sound.

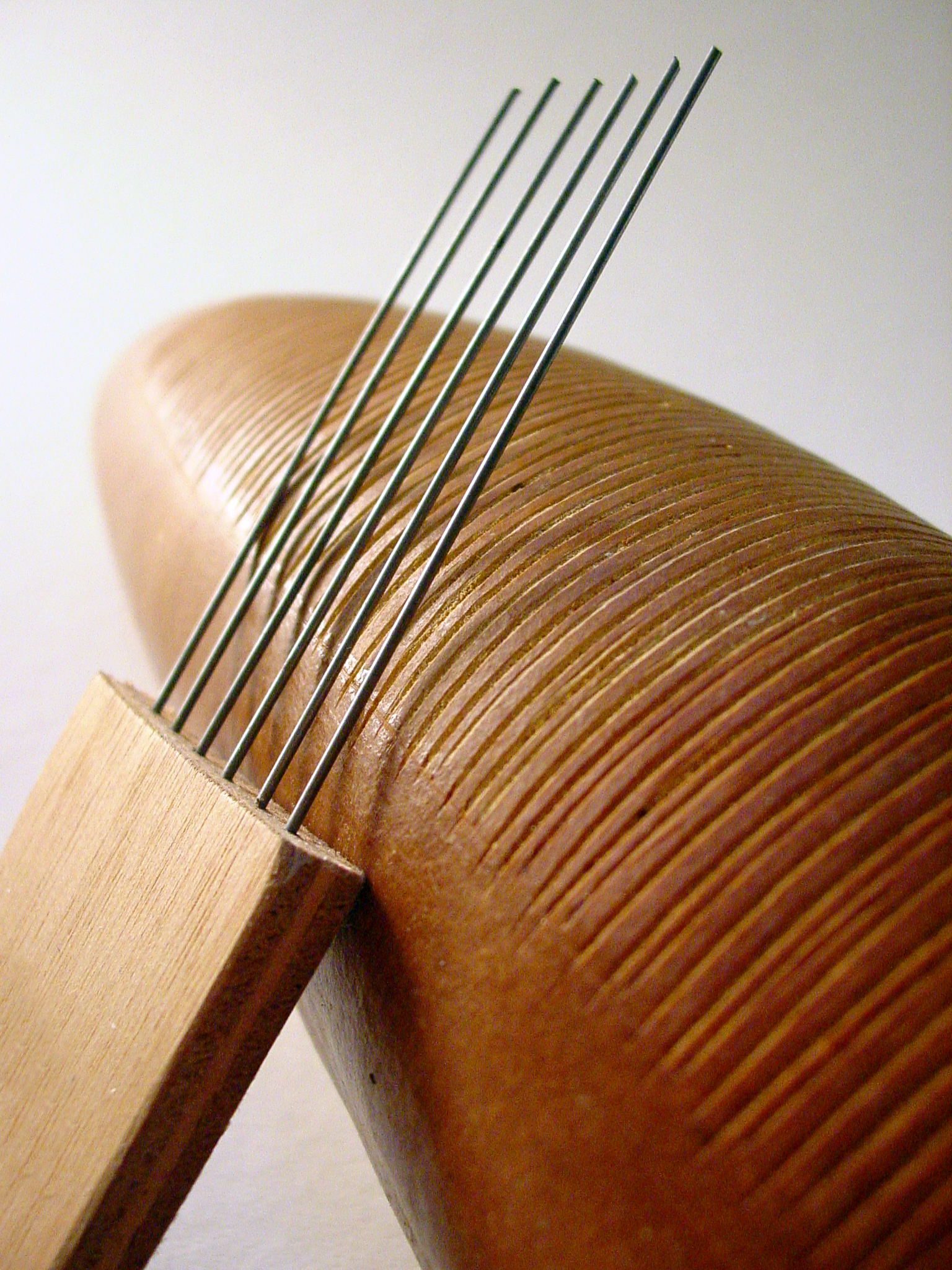

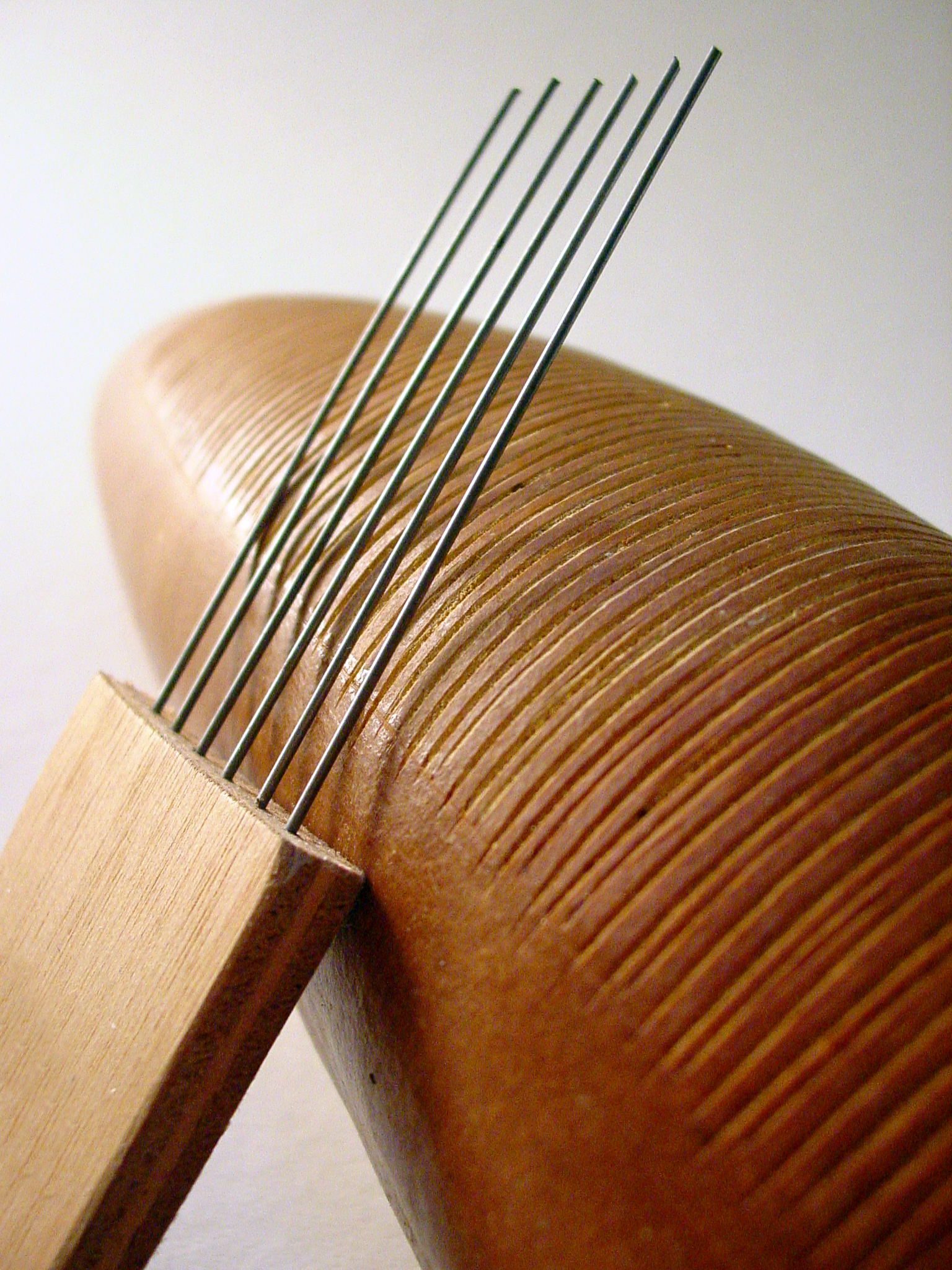

Varillero: The most distinctive feature of our güiro is the varillero or puya used to scrape it, which is “unique to Puerto Rico,” according to Amador Medina. It consists of a wooden handle, “often made with noble woods from the country,” and many fine wire or stainless steel prongs, which today are mainly made from piano strings to further refine the sound.

It’s unknown when a varillero of this type was first used in Puerto Rican music because “there’s no historical record,” but Amador Medina believes it could have been around or after the beginnings of Puerto Rican danza, in the mid-19th century, since in that rhythm “we already have a sound” similar to today’s güiro.

“Based on the prong you’re using, that’s the sound the güiro will produce,” explained Alvarado. “If the prong is too thick, the sound is deeper, more hoarse. The thinner it is, the higher-pitched the sound,” he added.

Of course, the Puerto Rican güiro was previously played with a cylindrical stick, as can be seen in the work El Velorio (The Wake/El Baquiné) by Francisco Oller, completed around 1893.

Another peculiarity was that, in the past, “the jíbaro would make two small holes so it would sound louder, because there was no amplification, and they also used them to insert their fingers,” explained Alvarado. “The holes aren’t made anymore,” he added, because “it changes the sound.” The holes give it a deeper sound, while not making them offers a finer sound.

Peñuelas: the Capital of the Güiro

If there’s anyone in Puerto Rico who has contributed to the history of the güiro, it’s Don Aníbal Alvarado, 82 years old, who started playing the instrument when he was barely 9 years old at the Promesas de Reyes (Three Kings Day promises) they held in his neighborhood in Peñuelas. His skill was such that neighbors would say: “Give the güiro to Miguel’s son, he really knows how to play,” Alvarado told Platea with laughter.

It wasn’t until several years later that he had his first güiro, which he scraped himself. He remembers it was in 1974, the year “the first güiro competitions were held in Peñuelas.”

Alvarado played with singer-songwriter Andrés Jiménez from Orocovis in his early days. In 1979, he founded the Rondalla Peñolana, with which he played for several years, and the Orquesta de Güiros de Puerto Rico, which still performs today. He also founded Aníbal Alvarado y su rondalla and, in 2000, the Conjunto de Cuerdas de Borinquen and Folklore Sin Fronteras.

He has güiros “by the hundreds” in a collection of 200 to 300 pieces, many of which he scraped himself. And he assures he’ll be playing and making güiros “until death caresses me.”

“In Peñuelas, thousands of students passed through my hands. And in Puerto Rico, I’ve given quite a few workshops, mainly in the southern region. Now I’m waiting for things to settle down so I can dedicate whatever little life I have left to that (teaching güiro),” said the musician, who loves to joke and is extremely proud of his Boricua heritage.

Modesty aside, I think you’d be hard pressed to find a güiro player in Puerto Rico who hasn’t picked up a thing or two from me… Peñuelas is known as the Capital of the Güiro, and modesty aside, that’s because of me.

Thanks to Alvarado’s legacy and his orchestras, Peñuelas is known as the Capital of the Güiro and they celebrate—in July—the Festival del Güiro for over 50 years. They also have a Monument to the Güiro on highway PR-385, a 27-foot bronze sculpture by artist Claudio Solano featuring a giant güícharo with a Puerto Rican flag.

From plena to Bad Bunny: where is the güiro today?

Don Aníbal shared that when he started with the güiro, people in his town would tell him: “You’re crazy.” However, “look where the güiro has reached,” with even an artist of Bad Bunny’s caliber making it sound around the world.

“The güiro is now in a better place than before. A güiro player can earn up to $300 per gig. But we still have a good stretch (to go),” said Alvarado, who believes the ones who came out best from Bad Bunny’s album are “those who play plena,” since now it’s a rhythm that’s respected even more.

About playing with Bad Bunny, he said: “If he calls me, we’ll work it out. I have the ability to adapt to all rhythms.”

For his part, Amador Medina emphasized that “what Benito has done on this last album isn’t a strange phenomenon,” as artists like Ricky Martin also included Puerto Rican music in their most commercial albums.

However, he considered that Benito’s distinctive approach has been creating from honesty, being transparent about his roots and reflecting the feelings of a people with the language and rhythm they understand and feel.

“I believe one of the greatest contributions of that album is that you hear the güiro doing things that aren’t traditional. Or you have patterns that are being worked on as you would work a percussion instrument in a pop music recording,” said the expert.

The musician acknowledged the “very prominent” sound of the güiro in Lo que le pasó a Hawaii, a song in which the instrument demonstrates the production value it can have.

For Amador Medina, “this project has served to strengthen and validate our people’s identity because it’s not just the music. It’s our customs, our traditions, recognizing that no matter how much of a rocker you are, how much of a reggaetonero you are, you know what a pitorro de coco is.”