Miguel Angel “Mike” Amadeo: the Puerto Rican who gave salsa its lyrics and soul

Whatever they’re going to give me

Let them give it to me while I’m alive

Don’t wait until

After I’m gone

I don’t want what happened

To Daniel to happen to me

Or to maestro Pedro Flores

Or to the glorious Rafael

— Excerpt from “Que me lo den en vida”If you’re one of those who have sung this El Gran Combo song at a party, you should know that behind this iconic lyric is the pen of Miguel Angel Amadeo, better known in the South Bronx and the Puerto Rican diaspora as Mike Amadeo.

Perhaps you know this story, as it has been covered by many, and since “Que me lo den en vida” was released, the tributes haven’t stopped coming. It’s as if Mike, owner of Casa Amadeo in New York, at 92 years old and still working daily at his store, underscores the importance of recognizing people’s work while they’re still alive.

The street in front of Casa Amadeo bears his name, the Puerto Rico Senate has recognized him, and almost every day he receives visitors wanting to interview him.

One of them was me. This Puerto Rican never lets go of his roots. So much so that when I called to coordinate, he answered with a simple “Buenas tardes,” as if he were tending his business on the island. “I kept my language; I had to,” he affirms with pride.

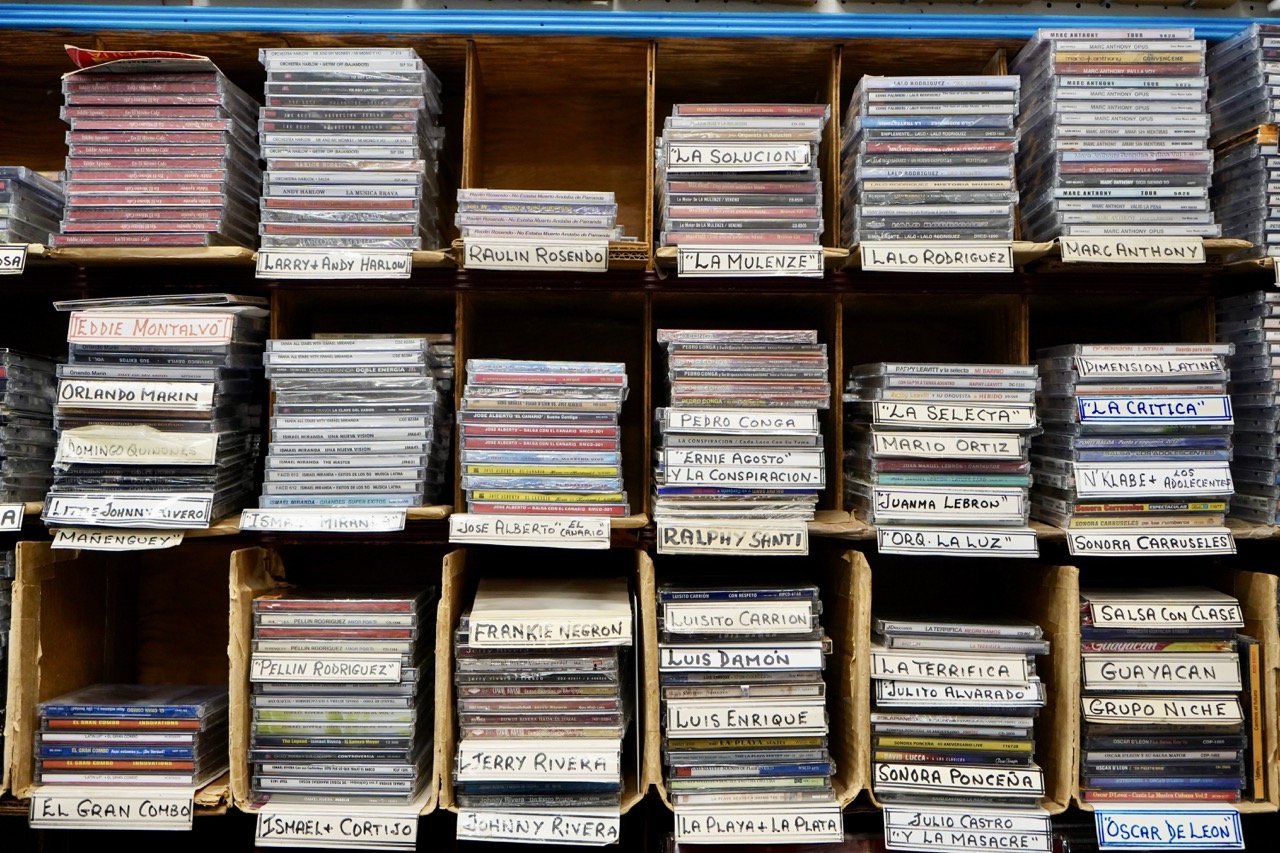

His store—almost a museum—located at 786 Prospect Ave. in the Bronx, is a showcase of stories and memories. A living tribute to Puerto Rican and Latin American music. There are photos of celebrities, instruments, and awards.

Here you can find vinyl records, CDs, instruments, and history. Seeing that space amid the daily hustle moved me: it seemed like a breath of fresh air, a reminder of the golden era and the deep roots that Puerto Ricans planted in New York.

Mike, accompanied by his son who shares his name, received me with grace and elegance to tell—once again—his story, which is the story of the Puerto Rican diaspora, one that defines an entire generation.

It’s easy to tell, but living it wasn’t. Time and Mike’s age make him doubt some details. But only some. Amadeo describes with precision the people and events that marked an era when Latin music was at its peak. When he sold hundreds of records in a week.

Upon entering his store, prominently displayed and imposingly, Mike establishes the true codes of the composers who must not be forgotten, paying tribute to them. Three large framed photos: Rafael Hernandez “El Jibarito” and Pedro Flores appear on each side, and in the center, himself, Miguel Angel Amadeo.

Mike Amadeo is who he is, in part, because he was the son of Titi Amadeo, his father, who arrived in the city in the 1920s to study medicine, although music always called him more strongly.

He was a first-class bohemian. He played in nightclubs around the city and made a name for himself, writing many hits. Being Titi Amadeo’s son opened doors for me.

— Mike Amadeo

“My father was a great composer. By the 1950s, he had already written a ton of famous songs in Cuba, Puerto Rico, and all of Latin America. Mostly boleros… that was Titi Amadeo’s music.”

The Discos Alegre Years

As he tells me, before the Fania boom, there was a key place for salseros: Discos Alegre. He started working there at 25, after serving in the army and playing for over eight years with the group Miguel Angel Amadeo y los Tres Reyes. Discos Alegre was a label with a physical store, Casa Alegre, where Mike was manager. Johnny Pacheco, Eddie Palmieri belonged there… “I auditioned Willie Colon at that place,” he recalls.

“That was the label that recorded all the orchestras. That’s where the ’60s and ’70s era comes from. Salsa as you know it. That’s where it all started, and that’s where I began writing guarachas and gave a song to Cheo Feliciano. That’s where what we call salsa began.”

The story is long and full of details. How did you get into music? I asked him. “My cousin gave me a guitar when I was 13, and that’s when Miguel Angel Amadeo was born… since that year, 1948, I’ve been writing songs.”

“I wrote about everything and everyone. I have hundreds of songs written for singers like Felipe Pirela, Roberto Ledesma, Celia Cruz,” he assures. Which is your favorite? He laughs. “You really put me on the spot. I have over 350 recordings.”

Casa Amadeo was born in 1969 when he bought the former Casa Hernandez. Since then, he has dedicated his life to music.

What does music mean to you? The question seems almost unnecessary. “For me, it’s my life. It’s what keeps me alive. There’s nothing more precious than people you’ve never met throwing you a party. Or having artists who recorded your songs celebrate you.” And as we talk, a neighbor arrives with pasteles and the shopkeeper next door brings his afternoon cafecito. “People love Mike a lot,” says his son.

At 92, he still works seven to eight hours daily. He keeps the store impeccable. “Everyone who comes in tells me how beautiful I keep it,” he comments with pride.

The record industry may have changed, but the consistency of Latin music—especially ours—remains.

Our son and our tumbao keep setting the rhythm and raising the bar. And in that pulse, in that heart, there still lives a man named Mike Amadeo.

Before we leave, he tells me: “I have a classic coming out.” He sings it for me. I can’t share it, but I can assure you there’s poetry, there’s soneo, and there’s life. “I hope to hear it performed by some artist before I die.”

“For me, it’s my life. It’s what keeps me alive. There’s nothing more precious than people you’ve never met throwing you a party.”