The unofficial anthems that tell the story of Puerto Rico

A journey through the songs that have accompanied generations of Puerto Ricans, both on and off the island, and which today are an essential part of our collective memory.

In the absence of Puerto Rican embassies, Puerto Rican musicians are our ambassadors, said journalist and writer Ana Teresa Toro. And indeed, Puerto Rican music undoubtedly crosses borders and defines our cultural identity and our idea of a nation.

Beyond the anthem La Borinqueña—both the romantic version by Manuel Fernández Juncos and the revolutionary version by Lola Rodríguez de Tió—there are many songs that have deeply permeated what we describe as Puerto Rican identity.

Together with historian Jorell Meléndez-Badillo, author of the book Puerto Rico: Historia de una nación (2024) and who wrote the historical context for the YouTube visualizations of each song from Bad Bunny’s DeBÍ TiRAR MáS FOToS, we take a historical tour of these songs that we could call unofficial anthems and delve into the reasons for defining Puerto Rican identity and the context in which they were written.

❝ We have produced a lot of culture, a lot of music. With these elements, we have managed to define our idea of nationhood. That is why it is important to affirm that Puerto Ricans, beyond political status, have created a complex idea of nationhood, and music is a fundamental element in that❞.Jorell Meléndez-Badillo, historian

for freedom eagerly awaits us.

que nos espera ansiosa, ansiosa la libertad.

La Borinqueña

“The Revolutionary Anthem”

Rodríguez de Tió’s famous poem, also known as the “revolutionary anthem,” is a “hymn of resistance” for the independence movement, which was never officially the anthem of Puerto Rico.

The poem was written in the context of the Grito de Lares (September 23, 1868), the first major “revolt for Puerto Rican independence,” but it took place in a broader Caribbean context of independence struggles against Spain, including Cuba’s, explained Meléndez-Badillo.

In fact, Rodríguez de Tió “evokes that Cuban-Puerto Rican solidarity” with her poem “Cuba and Puerto Rico are the two wings of a bird”, added the historian. This solidarity was not only in the struggle for independence, but also in cultural contexts, and it is in Cuba, her second homeland, where the poet went into exile and died.

Although it is usually sung to a dance rhythm, the music predates the poem. The composition is attributed to the Catalan Félix Astol Artés, although other versions indicate that it is by the composer Francisco Ramírez Ortiz. It is also said that both collaborated to compose the music for what became the anthem of Puerto Rico in 1952.

the daughter of the sea and the sun.

la hija del mar y el sol.

La Borinqueña

The official anthem

“It came at a time of political reorganization for Puerto Rico,” following the US occupation in 1898 and the establishment of a military government “where Puerto Ricans really had no say in politics,” explained Meléndez-Badillo. It was not until the passage of the Foraker Act in 1900 by the US Congress that a civilian government was established in Puerto Rico, something the historian called a “semi-democratic” government.

It is a romantic text that attempts to create a new historical memory, combining elements of nostalgia with the evocation of Puerto Rico’s natural beauty, all of which drives the discourse of nation building, Meléndez-Badillo explained.

It was in 1952 that the dance La Borinqueña was made official as the anthem with the musical arrangement by Ramón Collado, but it was not until 1977 that Fernández Juncos’ poem was established as the official lyrics of the anthem.

this land

where I had the privilege of being born!

esta tierra

donde tuve el privilegio de nacer!

La Tierruca

Contemplating the homeland

La Tierruca was first published in the book Canciones escolares (School Songs, 1912), created for Puerto Rico’s public schools—which at that time were beginning to spread throughout the countryside and cities—and in which Dávila, Fernández Juncos, and Dueño collaborated. It also appeared in the poetry collection Aromas del terruño (Aromas of the Homeland), considered one of the poet’s best.

It was published amid a boom in “romantic modernist poets” and had a similar tone to Fernández Juncos’ La Borinqueña in its appreciation of the country’s beauty, explained Meléndez-Badillo. It quickly became a kind of unofficial anthem, although it no longer has the recognition it had a few decades ago.

Although Dávila identified with annexationism and was mayor of Bayamón for the Republican Party, he had “very acute social and critical sensibilities,” according to the historian, as he also wrote critically about the conditions of Puerto Ricans in the United States. This can be seen in poems such as “Don’t Give Your Land to the Stranger” or ‘Nostalgia’ (“Mama! Borinquen Calls Me!”), which already begin to denote the feelings of Puerto Ricans in the United States.

*Music: La Tierruca. 1917. Audio. Retrieved from the Library of Congress.

which, when singing, the great Gautier

called the Pearl of the Seas,

Now that you are dying with your sorrows,

Let me sing to you too.

la que al cantar, el gran Gautier

llamó la Perla de los Mares,

Ahora que tú te mueres con tus pesares,

Déjame que te cante yo también.

Lamento Borincano

Puerto Ricans in the face of adversity

This lament—a passionate expression of pain—describes the suffering of Puerto Rican farmers during the Great Depression, a global financial crisis that lasted until the 1930s. It became one of the most outstanding expressions of Puerto Rican culture and the jíbaros.

For Meléndez-Badillo, the lyrics are a critique and “a portrait of the conditions Puerto Ricans lived in at that time,” although they do not necessarily call for political change. Like other unofficial anthems, it takes the element of nostalgia and the jíbaro as a cultural component.

It is one of the most famous songs by the prolific singer-songwriter and was recorded by Manuel “Canario” Jiménez and his band, with Pedro Ortiz Dávila “Davilita” as one of the voices, who was only 18 years old at the time. It has also been performed by a dozen artists, including Spain’s Plácido Domingo and Brazil’s Caetano Veloso.

It is included in the 2017 National Recording Registry of the Library of Congress.

without laurels or glory.

Beautiful, beautiful,

the children of freedom call you.

sin lauros ni gloria.

Preciosa, preciosa

te llaman los hijos de la libertad.

Preciosa

Love for Puerto Rico

In the midst of “the turbulent decade of the 1930s,” as Meléndez-Badillo calls it in his book Historia de una nación (History of a Nation), Hernández composed the song Preciosa in Mexico, one of the countries where he lived and spread his artistic talent. It is an ode to his country, expressing his longing to return. Together with Lamento Borincano, these are just two of his famous compositions that have been recorded as unofficial anthems.

“The 1930s were a decade of many changes in Puerto Rico,” the historian explained. Not only was the country going through the Great Depression and the impact of hurricanes, but there was also a coalition between the Socialist Party and the Republican Union Party to come to power, “the struggle for Puerto Rico’s independence intensified,” the Communist Party was founded, and the Nationalist Party was militarized.

It was a decade that saw the strengthening of the University of Puerto Rico (UPR) as the “leading center of learning,” the Chardón Plan, and programs such as PRERA and PRRA (federal agencies to combat poverty on the island) within the New Deal. The massacres of Ponce and Río Piedras also took place, as did the assassination of Colonel Elisha Francis Riggs, chief of the Insular Police, and the arrests of nationalists.

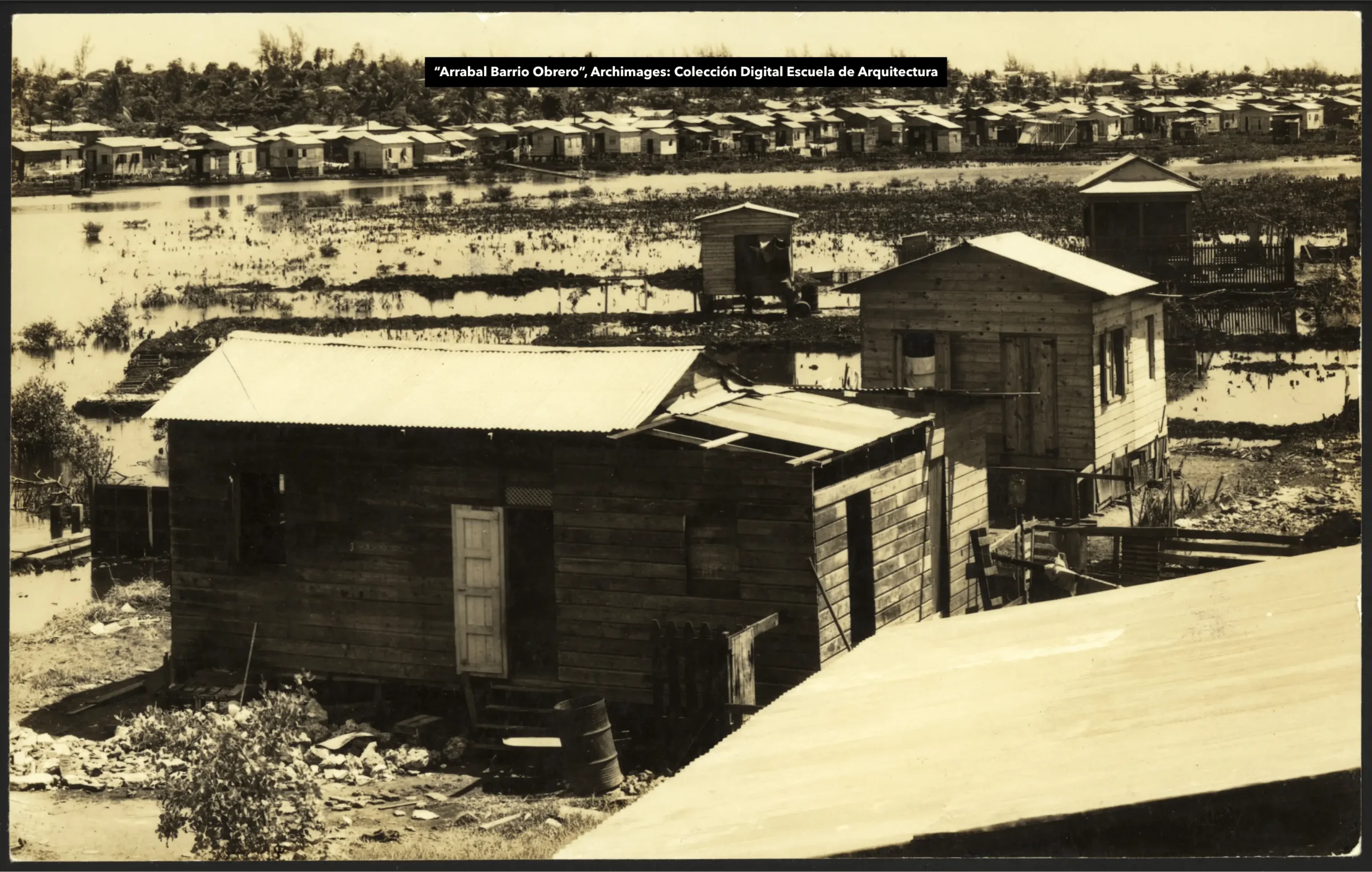

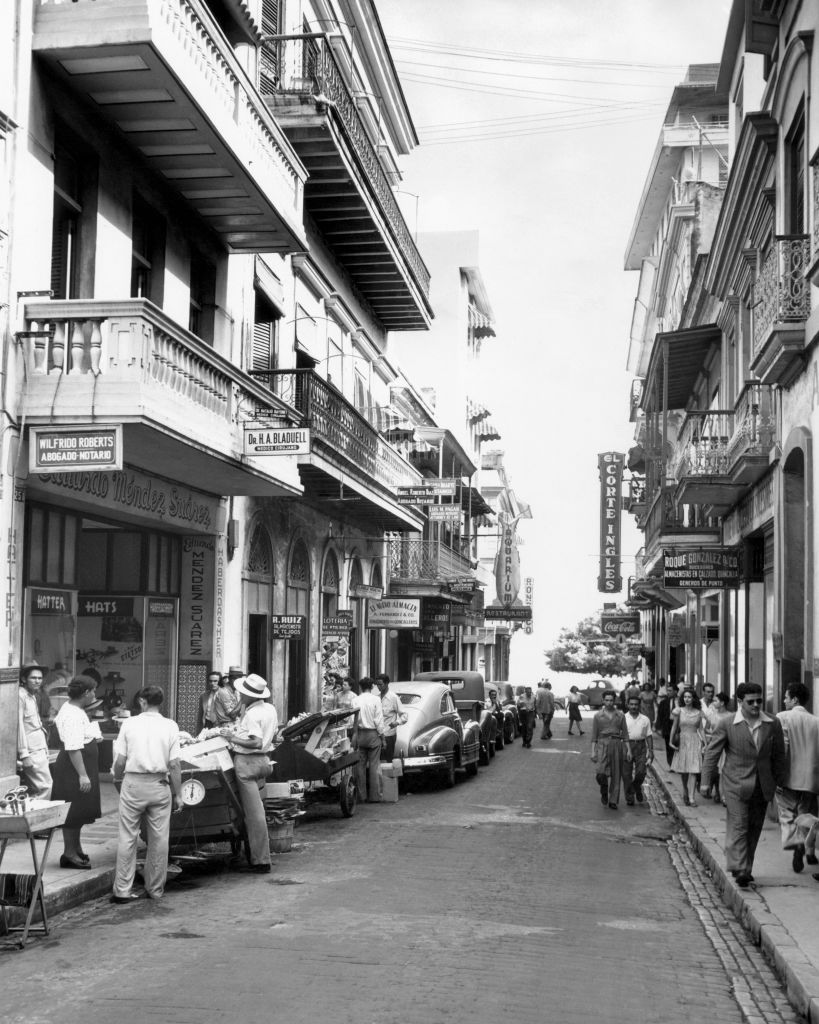

In addition, there was an internal migration from the countryside to the city, which was the “great prelude to the populism of the 1940s” and the Great Puerto Rican Migration, said Meléndez-Badillo.

Initially recorded by the Victoria Quartet, of which Hernández was a member, it became famous with the interpretation of Manuel “Canario” Jiménez. Today, it is Marc Anthony’s version that is most widely recognized, demonstrating that this song transcends political ideologies and unites Puerto Ricans in their admiration for their country.

“Hernández is a master of these compositions, of these lyrics that evoke that nostalgic feeling of the past,” he added.

but one day I’ll return

to find my love,

to dream again

in my Old San Juan.

pero un día volveré

a buscar mi querer,

a soñar otra vez

en mi Viejo San Juan.

In My Old San Juan

The Longing to Return

There are two aspects that mark this composition: World War II (1939-1945), with hundreds of Puerto Ricans active in compulsory military service—including Estrada Suárez’s brother— and the Great Puerto Rican Migration (between 1940-1960), considered “the first large-scale air migration in human history,” with more than 800,000 Puerto Ricans leaving the archipelago by plane, Meléndez-Badillo noted.

*Music: Recording of the performance by the Conjunto de Cuerdas Típicas de Puerto Rico at El Romance Club, Chicago, Illinois, 1977. Retrieved from Library of Congress.

Although “Puerto Rico is a diasporic nation that has been in constant motion,” even in pre-Columbian times, according to Meléndez-Badillo, it was in the 1940s that this migration intensified and Old San Juan became a focal point for reflecting on this physical and cultural displacement that persists to this day.

The impact of the song was global, so much so that it was translated into French, English, and German. It has hundreds of versions in rhythms such as bolero, tango, and ranchera. And in the 1980s, it officially became the anthem of San Juan.

if I am far from your silent palms,

I want to return, I want to return.

si me alejo de tus palmas silenciosas,

quiero volver, quiero volver.

Verde Luz

The new struggle for independence

In the midst of the “new struggle for independence” and our nation’s migratory ups and downs, “Verde Luz stems from the sensitivity that emerged in Puerto Rico after 1959 with the Cuban revolution, which, although it took place in Cuba, had an enormous cultural impact, not only in Puerto Rico but throughout the Americas and the world,” the historian pointed out.

Cabán Vale wrote it when he was just 24 years old, during his time as a university student and when he was about to emigrate to New York, in the context of protest songs, student struggles, and “other forms of political expression through music,” added Meléndez-Badillo. It was the singer-songwriter himself, who was the subject of federal surveillance, who immortalized it and catalogued it as a symbol of the struggle for Puerto Rico’s independence and self-determination.

“The people who would advocate for Verde Luz as a second anthem come from a particular ideology… an independence sector that feels it is their anthem,” said the historian.

what a beautiful flag is my Puerto Rican flag.

qué bonita bandera es mi bandera puertorriqueña.

What a beautiful flag

A diasporic anthem

After the Great Puerto Rican Migration, Meléndez-Badillo believes that this plena became a “diasporic anthem” that appeals to a nationalism “that does not need a discourse on the status of Puerto Rico.” This takes on greater importance in the diaspora, when many are searching for a sense of belonging and find themselves needing to reaffirm their Puerto Rican identity, with the flag as their main resource.

Morales Ramos, famous for his influence on plena and jíbara music, wrote this song to highlight the pride of displaying the Puerto Rican flag, which only two decades earlier had been banned. And the song’s success, according to the historian, is that it expresses “a cultural nationalism that is detached from the divisive conversation about Puerto Rico’s political status.”

This is one of the most popular plena songs at the Puerto Rican Day Parade in New York and was the song played when Puerto Rican-born astronaut Joseph Acabá went into space in 2009.

the pride I feel

in being Puerto Rican.

And that my thoughts,

no matter where I go,

escape to the little island…

el orgullo que siento

de ser puertorriqueño.

Y que mi pensamiento

no importa dónde voy

se fuga hacia la islita…

Dreaming of Puerto Rico

It’s time to return

Like several of the previous songs, this bolero “captures that moment of the diaspora in the United States dreaming of Puerto Rico,” said Meléndez-Badillo.

“For me, as a member of the diaspora, it’s very complex because sometimes I don’t feel at home either here or there (in Puerto Rico or the United States)… Through cultural and artistic production, various artists, musicians, etc., have affirmed that notion of Borinquen, of homeland, and that’s why the flag is so important in our diasporic communities,” he added.

Jacqueline Capó, daughter of Bobby Capó, says that the composer wrote the song at the request of his wife, Irma Vázquez, while they were living in New York. He told her that Noel Estrada had En mi Viejo San Juan and Rafael Hernández had Preciosa and Lamento Borincano, but he had not yet written anything for Puerto Rico. This is how Soñando con Puerto Rico came about, which was included on the album Despierte borincano, along with songs such as Mi Borinquen and Qué bueno es ser borincano.

Beyond the iconic Piel Canela and El Negro Bembón, Capó was one of the most famous Puerto Rican composers, connecting with that Puerto Rican identity anywhere in the world.

I am the son of palm trees,

of fields and rivers,

and of the song of the coquí.

soy hijo de las palmeras,

de los campos y los ríos,

y del cantar del coquí.

Amanecer borincano

The evocation of the jíbaro

Following the migrations not only from Puerto Rico to the United States, but also from the Puerto Rican countryside to the city, a song emerged that evoked “that notion of a deep Puerto Rico” and “the return to the countryside, to rural life, to the jíbara question,” Meléndez-Badillo pointed out.

In the 1970s, what is known as cyclical migration took place: the return of those who had left years before. “Many people from the diaspora began to return to Puerto Rico. It was also a time of political and economic transition. In 1968, we had the first victory of the New Progressive Party (PNP),” said the historian.

“With the creation of the slums, we also have the occupation of spaces with Villa Cañona and Villa Sin Miedo, which are marginalized, poor communities that occupy spaces,” he added.

During this transition period, there was a call for “statehood for the poor, jíbara statehood,” at a time when “it was clear that Puerto Rico’s industrialization project, if it had not failed completely, as it did in the 1980s, was already running out of steam.” There is a romanticization of the jíbaro and the countryside, even if it is as a nostalgic cultural element.

I would be Borincano

even if I were born on the moon.

yo sería borincano

aunque naciera en la Luna.

Boricua on the Moon

Puerto Ricans are born where they want to be

After decades of Boricuas being born in the United States, some of them without ever having set foot on the island or having Spanish as their first language, a poem emerges that reaffirms that Boricuas are born where we want to be.

It was inspired by those who left in search of a better life and by the former prisoners of the National Liberation Armed Forces (FALN, “los Macheteros”), whom Corretjer visited. In addition, it was written only two years after the murders of independence activists in Cerro Maravilla.

The poem not only “evokes that patriotic nostalgia” and the “search for what it means to be Puerto Rican”; it is “highly political because part of the context in which it was written is the armed struggle for Puerto Rico’s independence,” explained Meléndez-Badillo.

“(Boricua en la luna) is a love letter to those people who were giving their lives in the struggle,” he added, and it is an answer to that constant question of “how we think about Puerto Rican identity.” For the historian, “this is my anthem” because it remains as relevant as it was in the 1980s, considering that there are more Puerto Ricans living abroad than in the archipelago.

The poem was set to music in 1987 by singer-songwriter Roy Brown, an ally of the student and independence struggles, and has also been performed by groups such as Fiel a la Vega.

❝ Puerto Rico is a diasporic nation that has been in constant motion, and these songs accompany us wherever we go, reminding us of who we are and where we come from❞.— Jorell Meléndez-Badillo, historian

Other songs that identify us

Will they stand the test of time?

❝ Many people may see anthems as something more solemn, more serious, but I think they also represent who we are❞.

– Jorell Meléndez-Badillo, historianLos colores de mi tierra

Alberto Carrión

The Harris Paint commercial that became a generational anthem for those born in the 1980s.

Los colores de mi tierra

Alberto Carrión, 1993

The Harris Paint commercial, composed by Alberto Carrión—who also composed Amanecer Borincano—has a special place in the hearts of that generation born in the 1980s.

“I remember as a teenager jokingly standing up in the cinema with my friends and putting our hands on our hearts because I think the song appealed to a similar sensibility to that of Fernández Juncos with La Borinqueña, evoking the colors, flora, fauna, and everyday life.”

Meléndez-BadilloEven today, versions of this song continue to be created because it is a portrait of the Puerto Rico we long for or a memory of our childhood.

El Wanabí

Fiel a la Vega

A song that appeals to the importance of fighting to move forward, with sensitivity for the working class.

El Wanabí

Tito Auger and Ricky Laureano, 1996

Composed by Tito Auger and Ricky Laureano, it is one of the songs that appeals to the importance of fighting to move forward.

“It has a sensitivity for the working class, for those who move from the countryside to the city and want to get involved.”

Meléndez-BadilloAlthough it does not directly speak of the pride of being Puerto Rican, it marked a generation that was trying to prove what they were made of in the decade of Dayanara Torres as Miss Universe, the Puerto Rico Dream Team’s championship in the Caribbean Series, the “tough on crime” policy, and the explosion of Humberto Vidal in Río Piedras.

Who doesn’t feel patriotic?

José Rafael López Figueroa

This plena demonstrates the pride of being Puerto Rican, a must at the Las Fiestas de la Calle San Sebastián.

Who doesn’t feel patriotic?

José Rafael López Figueroa, 1998

Like other compositions on this list, this song expresses the pride of being Puerto Rican and expressing that feeling, said Meléndez-Badillo.

This plena by José Rafael López Figueroa was popularized by Andy Montañez and is often one of the most performed songs at Las Fiestas de la Calle San Sebastián.

Gasolina

Daddy Yankee

The song that catapulted reggaeton to worldwide fame and marked a moment in Puerto Rican popular culture.

Gasolina

Daddy Yankee and Eddie Dee, 2004

“Daddy Yankee’s Gasolina marked a moment in Puerto Rican popular culture. Many people may see anthems as something more solemn, more serious, but I think it also represents who we are.”

Meléndez-BadilloGasolina was written by Daddy Yankee (Ramón Ayala) and Eddie Dee (Eddie Ávila) for the album Barrio Fino. In 2021, it was included as one of the 500 greatest songs of all time, and in 2023, it was added to the National Recording Registry of Congress.

Despacito

Luis Fonsi and Daddy Yankee

A fusion of reggaeton and Latin pop that topped the charts in 47 countries and became a global phenomenon.

Despacito

Luis Fonsi, Daddy Yankee, and Erika Ender, 2017

Despacito was composed by Luis Fonsi, Daddy Yankee, and Erika Ender, and is a fusion of reggaeton and Latin pop that topped the charts in 47 countries. The video became one of the most viewed and liked of all time.

It represents the global reach of our music and culture in the 21st century.

Hijos del Cañaveral

Residente

It revisits patriotic sentiment and a return to roots, to the countryside and to the jíbaro in times of crisis.

Hijos del Cañaveral

René Pérez (Residente), 2017

Beyond Latin America (2010) by Calle 13, which became a kind of Latin American anthem, Hijos del Cañaveral—composed by René Pérez—takes up that patriotic feeling and that return to the roots, to the countryside, and to the jíbaro.

“People took ownership of the song… the song surpassed the artist… it went beyond the limits of the genre.”

Meléndez-BadilloFor the historian, the song reached those who did not necessarily follow Residente and has been performed in various parts of the archipelago, in a decade marked by economic and fiscal crisis, Hurricane Maria, and the imposition of the Fiscal Oversight Board.

🎧 Listen to our playlist

The unofficial anthems of Puerto Rico